Chemical compounds, diets, physical training, and genetic engineering have all proven successful in extending lifespans and healthspans in animal species. Among these approaches, lifestyle factors are the first ones we can start to apply in real life.

Supertrends has compared studies based on different protocols to ensure that the advice we give is reasonable enough for our readers to practice on a long-term basis. Yes, these adjustments will require a certain degree of discipline, but we think they are worth the efforts if an additional 5-10 years of healthy life can be added to your lifespan.

When you eat and what you eat

When you eat and what you eat

A significant share of the many available nutrition guidelines is based on intuition rather than science. Often, diets come and go like fashion trends, yet diet is one of the most critical lifestyle interventions for good health. Under the scrutiny of cell biology, these days, scientists talk more about when you eat than what you eat.

From calorie restriction to intermittent fasting

Calorie restriction (CR) refers to a dietary regimen that is low in calories without undernutrition. Since the 1930s, its effect of extending mammalian lifespan and delaying the onset of age-related diseases has been recognized. Among the approaches that extended lifespans and healthspans in different animal species, CR is the only non-genetic intervention that produced consistent benefit across a variety of species. The benefits of CR include cellular stress activation, improved autophagy (the process that removes damaged or unnecessary components within the cell), and hormone regulation.

However, few people make full use of the benefits of the CR regimen. After all, CR means cutting back average food intake by 25 to 50 percent. After extensive research, the good news is that intermittent fasting (IF) can yield similar, if not more benefits than CR.

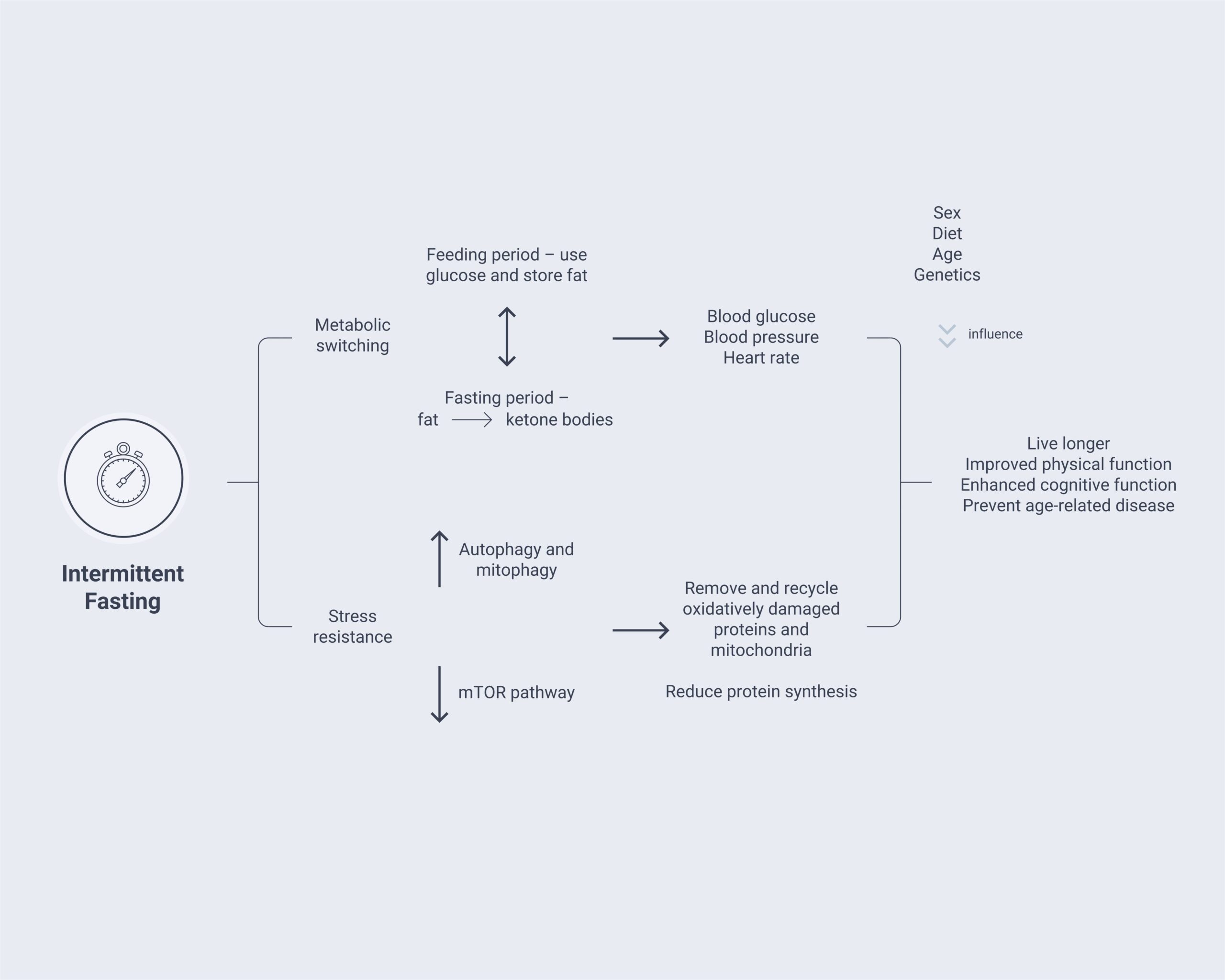

The benefits of IF involve mainly two mechanisms – metabolic switching and cellular stress resistance.

Metabolic switching - After we eat, our body uses glucose as energy and stores fat as triglycerides. During fasting, triglycerides are broken down into fatty acids and glycerol as energy carriers. Fatty acids, in turn, are converted into ketone bodies as a major source of energy. Ketone bodies can also profoundly influence health and aging by regulating many proteins and molecules. These benefits include improvements in glucose regulation, blood pressure, and heart rate. Ketone bodies also have implications for brain health as well as for psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders.

Stress resistance - Fasting is a personal challenge and creates stress for the human body. Repeated exposure to stress can induce adaptive responses at the cellular level, including stimulation of autophagy and mitophagy (the selective degradation of mitochondria by autophagy) while inhibiting the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) protein synthesis pathway. These responses work together to switch our cells from reproduction mode to survival mode, with oxidatively damaged proteins and mitochondria removed and recycled. At the same time, protein synthesis is reduced to conserve energy and resources.

When to eat

There is not yet a validated “best” IF regimen with minimum restriction and maximum benefit. The most common plans used for human studies are:

- The 16/8 diet – fasting every day for 14-16 hours and restrict the daily eating period to 8-10 hours.

- The 5:2 diet – eating normal meals for five days and restricting calorie intake (500-600 calories/day) for two days (could be consecutive days or non-consecutive days).

- Eat-stop diet – 24-hour fasting, once or twice per week.

The most widely adopted IF plan is the 16/8 plan. It is closer to our usual eating habits. It is also the simplest, as you don’t have to count calories. Many scientists and medical doctors who study longevity have adopted this lifestyle intervention themselves.

The 16/8 plan means you will skip breakfast. For example, your eating window can be from 1 pm to 9 pm, or from 12 pm to 8 pm. It is recommended to adapt to this IF regimen gradually. Below is an adoption plan to help you with this lifestyle intervention.

We have prepared a step-by-step adaption example for a person who usually eats three meals and a snack after dinner. The principle is to gradually delay the first meal until the eating window is restricted to 8 hours. You can ingest liquids with no calories, such as black coffee, tea, and water, during the fasting period.

| Breakfast e.g., 7 am | Lunch e.g., 1 pm | Dinner e.g., 7 pm | Snack e.g., 9 pm | Sleep e.g., 11 pm | |

| Week 1 | Same | Same | Same | Reduce snack size to half | Same |

| Week 2 | 8 am | Same | Same | No snack | Same |

| Week 3 | 9 am | Same | Same | No snack | Same |

| Week 4 | 10 am | Same | Same | No snack | Same |

| Week 5 | 11 am | Same | Same | No snack | Same |

Examples of the other two popular IF plans are shown in the following:

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun | |

| IF adoption example | Normal | Women - 500 calories Man - 600 calories | Normal | Normal | Women - 500 calories Men - 600 calories | Normal | Normal |

| Eat-stop diet | Normal | 24-hour fast | Normal | Normal | 24-hour fast | Normal | Normal |

There are, however, people with certain conditions who should not try IF, or should consult their physician before making the decision:

- People who need sufficient calories because they are underweight, under 18 years old, an athlete in training, pregnant, or breastfeeding

- People who have certain medical conditions – eating disorders, type 1 diabetes, other severe medical conditions

What to eat

We do not provide specific nutritional plans to fight aging. This, of course, does not mean that what you eat is not important. We do not offer specific plans because there is no clear and convincing scientific evidence yet on what kind of food can extend our lifespan. However, we do present here some trends related to food choices and anti-aging. In general, we can say that a healthy balanced diet should include more vegetables, fruits, and fish, and less processed food, saturated fat, sugar, and salt.

The bad and good amino acids

Recent research has revealed that certain amino acids, the building blocks of protein, can also function as signals at the cell level to influence the aging process.

Methionine is an essential amino acid in humans. It is essential to our health, but too much of it is not desirable. Methionine restriction was found to delay aging and extend healthspan in mammals. It was also found to inhibit cancer cell growth. High levels of methionine can be found in eggs, meat, fish, and some plant seeds, with chicken and fish having the highest methionine levels. Most fruit and vegetables contain very little methionine. It is possible to achieve methionine restriction using a vegan diet (a diet that contains only plants and foods made from plants).

For people who do not want to give up meat and animal products, the good news is that supplementation with glycine can mimic methionine restriction to extend lifespan. Glycine is a non-essential amino acid that can be produced naturally in the body. Since much more research is needed to understand the signaling pathways activated by amino acids, we will not recommend any specific measures.

Sources

- Golbidi, S., Daiber, A., Korac, B. et al. 2017. Health Benefits of Fasting and Caloric Restriction. Curr Diab Rep 17, 123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-017-0951-7

- Shetty, A.K., Kodali M.,, Upadhya R., and Madhu L.N., 2018. Emerging Anti-Aging Strategies Scientific Basis and Efficacy. Aging Dis. 9(6): 1165–1184. https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2018.1026

- De Cabo R., Mattson M.P., 2019. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease. N Engl J Med. 2019 Dec 26;381(26):2541-2551. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1905136.

- Canfield CA., Bradshaw PC., 2019. Amino acids in the regulation of aging and aging-related diseases. Translational Medicine of Aging, Volume 3, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tma.2019.09.001.

How to get the most health benefit from minimum exercise

How to get the most health benefit from minimum exercise

Most of us start to lose our muscles after age 30 and experience decreased muscle strength and endurance. The medical term for this condition is sarcopenia. Normally, we lose around 3 percent of our muscle tissue per decade. These age-related muscle changes typically accelerate around age 75.

The primary treatment for muscle aging is physical exercise; classically, weight training is most effective in muscle maintenance. However, there is no consensus on the optimal training parameters. The thought of having to run for hours to receive benefits may put many people off from even starting an exercise routine. But if I tell you that you only need to exercise as little as 20 minutes, two or three times per week, suddenly things don’t look so unachievable.

What type of exercise?

In 2020, the Generation 100 study was published. It was the first major study on exercise and aging in humans. It taught us a lot about whether exercise can make us live longer and healthier and which kind of exercise is most beneficial for the elderly.

The Generation 100 study involved more than 1,500 elderly men and women and ran for five years. It compared the effects of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and moderate intensity training in people aged 70-75. It found that both the physical and the mental quality of life were better in the HIIT group. The HIIT group also had a lower death rate.

How long should the exercise last?

Intensive exercise is beneficial, but it cannot last too long, especially for the elderly. Will a burst of short exercise be enough to do the trick? Another study by the Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital answered that question.

This study found that 12 minutes of exercise with increased intensity were enough to influence 80 percent of the metabolic markers in the blood. This can have beneficial effects on body functions such as insulin resistance, oxidative stress, vascular reactivity, inflammation, and longevity.

Supertrends recommendations for physical exercise

For healthy adults, HIIT is one of the best exercise routines, offering anti-aging benefits as well as a flexible routine that is easy to carry out. HIIT workouts combine a few cycles of high-intensity exercise with intervals of low-intensity breaks. This type of exercise has not only proven to have a greater health benefit, but it is also less time-consuming. These exercises can be done either in a gym or at home.

Exercise type

Ideally, exercise should involve large muscle groups. For people who don’t work out regularly, treadmills and exercise bikes are excellent choices, as their resistance (workload) can be adjusted easily. HIIT can be done without equipment, using movements such as burpee or jump squat, but these movements are harder to perform. They could also be a little bit risky, especially for the elderly or people who don’t work out regularly.

Exercise intensity

An exercise intensity target can be set up by heart rate (HR). Smartwatches made it very easy to measure HR. You can also calculate the HR by counting your pulse. The most accurate method to determine exercise intensity level would be to do a stress test in a medical center. The benefits of doing a stress test under medical supervision are to ensure safety while exercising at high intensity and to get an accurate maximum HR to set as the exercise target. Another way of calculating maximum HR is by subtracting your age from 220.

The next step is to know your resting HR by counting how many times your heart beats per minute while resting. Subtract your resting HR by your maximum HR is your HR reserve (HRR).

When the HRR is calculated, one can set an HR target for the high-intensity that is equal to resting HR plus 80-90 percent of HRR; and an HR target can be set for the low-intensity period that is equivalent to resting HR plus 60-70 percent of HRR.

For a 50-year-old with a resting HR of 70 beats per minute, the HRR is 220-50-70 = 100. A conservative target HR for a high-intensity period is 70 + 80 percent x 100 = 150; the target HR for a low-intensity period is 70 + 60 percent x 100 = 130.

Another way of determining the exercise intensity is by using the Borg Scale. This is a graded rating system for perceived exertion, which can be done conveniently without the need to calculate HR.

| How you might describe your exertion | Borg rating of your exertion | Examples (for most adults <65 years old) |

| None | 6 | Reading a book, watching television |

| Very, very light | 7 to 8 | Tying shoes |

| Very light | 9 to 10 | Chores like folding clothes that seem to take little effort |

| Fairly light | 11 to 12 | Walking through the grocery store or other activities that require some effort but not enough to speed up your breathing |

| Somewhat hard | 13 to 14 | Brisk walking or other activities that require moderate effort and speed your heart rate and breathing but don’t make you out of breath |

| Hard | 15 to 16 | Bicycling, swimming, or other activities that take vigorous effort and get the heart pounding and make breathing very fast |

| Very hard | 17 to 18 | The highest level of activity you can sustain |

| Very, very hard | 19 to 20 | A finishing kick in a race or other burst of activity that you can’t maintain for long |

Source: Borg G.A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1982; 14:377-381.

In the Generation 100 study, a Borg score of 16 was used for the high-intensity exercise, and 12 was used for low-intensity breaks. We think these levels are suitable for the elderly and people who don’t exercise often. If you want to go with higher intensity, it probably is a good idea to work with a trainer. Sometimes, exercise does cause strains and sprains. It is also a good idea to have a stress test prior to starting the exercise to exclude any heart conditions.

Exercise duration and frequency

All exercise sessions should start with a five- to ten-minute warm-up and end with another five to ten minutes of cooling down. The activities in these two periods should be with very little effort, such as slow walking.

After the warm-up, you move into the cycles of HIIT. In the Generation 100 study, there were 4 cycles of 4 minutes of high-intensity exercise plus 3 minutes low-intensity break for each cycle. This can serve as an example. Other reports recommend exercises with a shorter timeframe. However, we do think the total high-intensity exercise time should not be less than 12 minutes.

The exercise can be repeated two or three times a week. At least one day of rest is needed between exercise days to allow the muscles to recover and repair. It is also good to make sure you have enough protein and liquid intake on the exercise day.

An example of a HIIT plan example for a 50-year-old person with a resting HR of 70 beats per minute would be:

- Start with ten minutes of brisk walking or biking.

- Increase the speed and slope/resistance to having an HR at 150 per minutes, keep exercising for four minutes – reduce the speed and slope/resistance to have an HR at 130 per minutes, keep exercising for three minutes.

- Repeat this cycle four times.

- Finish with another five minutes of slow walking or biking.

For people who have chronic conditions such as diabetes, obesity, heart conditions, etc., it is essential to get medical advice before starting the HIIT.

Other lifestyle factors and their combination

Other lifestyle factors and their combination

The theory that mild stress can extend lifespan has been around for some years. Evidence shows that exposure to mild radiation, heat, cold, hypergravity, etc., can increase longevity in animals such as fruit flies. The reason why mild stress could benefit aging is not yet clear, except that cold exposure is known to increase the activity of brown fat tissue (the good fat that can transfer energy from food into heat). Another interesting finding is that combining two mild stresses with positive effects on aging can be more efficient than stress alone.

Cold and heat

Examples of mild stressors are radiation, cold, heat, hypergravity, and hypoxia. We can also consider calorie restriction and exercise as putting our body through mild stress. Other than calorie restriction and exercise, which we already discussed, cold and heat are the only ones that are easily accessible. There is scientific evidence that cold showers, sauna bathing, contrast showers have health benefits related to the cardiovascular system, neurocognitive abilities, the immune system, and weight. However, there is little evidence of cryotherapy's aesthetic benefits, which are asserted by some medical spas and wellness centers. There is also not enough data on the optimal temperature and duration of the cold/heat exposure.

Our recommendations are that cold showers, sauna visits, and contrast shower are worth trying. However, they should be used in a sensible way.

Combining lifestyle factors

It has been proven that combining CR or IF and exercise is not only more efficient than each of them alone but can also preserve muscles from CR-induced weight loss. The general opinion is that exercise should only be done outside of fasting periods to ensure there is enough energy supply.

Other possible combinations are exercising in a cold environment or taking a cold shower or sauna after exercise. Since an exercise must be relatively high in intensity to have an anti-aging effect, it may not be practical to combine exercise and heat.

Sources

- WebMD, Sarcopenia with Aging. https://www.webmd.com/healthy-aging/guide/sarcopenia-with-aging

- Stensvold D., Viken H., Rognmo Ø., et al. 2015. A randomised controlled study of the long-term effects of exercise training on mortality in elderly people: study protocol for the Generation 100 study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007519. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007519

- Nayor M., etc. 2020. Metabolic Architecture of Acute Exercise Response in Middle-Aged Adults in the Community. Circulation. 142:1905–1924. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050281

- Minois, N. 2000. Longevity and aging: beneficial effects ofexposure to mild stress. Biogerontology 1, 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010085823990

- Le Bourg, É. 2012. Combined effects of two mild stresses (cold and hypergravity) on longevity, behavioral aging, and resistance to severe stresses in Drosophila melanogaster . Biogerontology 13, 313–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-012-9377-4

- Laukkanen J.A., Laukkanen T., Kunutsor S.K., 2018. Cardiovascular and Other Health Benefits of Sauna Bathing: A Review of the Evidence, Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Volume 93, Issue 8. Pages 1111-1121, ISSN 0025-6196, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.04.008.

- O’Connor M., Wang JV., Saedi N., 2018. Whole‐ and partial‐body cryotherapy in aesthetic dermatology: Evaluating a trendy treatment. J Cosmet Dermatol.18: 1435– 1437. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.12821

- Weinheimer E.M., Sands L.P., Campbell W.W., 2010. A systematic review of the separate and combined effects of energy restriction and exercise on fat-free mass in middle-aged and older adults: implications for sarcopenic obesity, Nutrition Reviews, 68:7, 375–388, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00298.x

- Marzetti E., Lawler J.M., Hiona A., Manini T., Seo A.Y., Leeuwenburgh C., 2008. Modulation of age-induced apoptotic signaling and cellular remodeling by exercise and calorie restriction in skeletal muscle. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 44:2, 160-168, ISSN 0891-5849, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.028.